How and When to Use Quotations

My first book chronicled the aftermath of a violent crime. I spent hundreds of hours with the Tac Squad, the doctors, the lawyers, the neighbors, the friends, the teenage boy's flight instructor; and most of all the surviving members of the family, especially the father. I had scores of hours on tape of him describing the call, rushing to the scene, up to the hospital, down to the morgue, then back up to the ICU to watch his 16-year-old son hang at the edge of life for the next six months.

For three years, I tried to write of the father's experiences in my own words, but it was not working. Finally, I decided that whenever he entered the story, I would step back and let him talk directly to the reader. It was one of my wiser decisions. Nothing I said or the way I said it would ever move a reader as much as what he said and the way he said it. His strong voice gave the book its power:

I don't know how you describe the feeling. I don't know how in the hell you can describe feelings that rip your guts. It's remorse and despair and agony in your heart, and you get real pain in your chest. When you hear someone say they've got a heartache, they've got a heartache, a heartache. It aches. It hurts, it pains, it throbs. When I looked at my wife, I had real pain in my heart.

Whether quoting a statute, a report, or the key figure in a book, our first thought should be to frame the quotation in our own words. I would not touch the quotation above; but rarely do we need to quote feelings at such depth. The quotation below is more like what most of us face in our daily work lives, and a great example of how we can often say it better in our own words:

Congress declared that BLM’s public lands were to be managed “on the basis of multiple use.” Multiple use management requires “a combination of balanced and diverse resources uses,” including “recreation, range, timber, minerals, watershed, wildlife and fish, and natural scenic, scientific and historical values.”

We can condense it in our own words to this:

Congress mandated that BLM open public lands to multiple use, which requires balancing the private development of natural resources with the public’s right to enjoy the land’s natural beauty.

If we cannot write it as eloquently or as poignantly or as accurately as the original, our next thought should be to pare the quotation to its dramatic essence; but remember one screenwriting law from Billy Wilder, writer/director of SunsetBoulevard, The Apartment, and Some Like It Hot: Never use a Voice Over to describe what the audience sees on the screen. Translated for the rest of us: Never preface a quotation with words the reader will see in the quotation:

Hamilton is entitled to its attorneys’ fees and costs as a matter of right: “Except as otherwise expressly provided by statute, a prevailing party is entitled as a matter of right to recover costs in any action or proceeding.”

Here, we remove the overlap and use only the essence of the quotation:

As the prevailing party, Hamilton “is entitled as a matter of right to recover costs in any action or proceeding.”

Last: When you do quote, quote only the pithy parts. Many of us quote long passages, then bold the pithy parts. Whoever wrote the example below ignores this rule and Billy Wilder:

Plaintiffs’ Agreements required that Plaintiffs’ claims be resolved at arbitration and mandated that following arbitration, the prevailing party receive its attorneys’ fees and costs:

. . . [a]ny controversy, claim or dispute arising out of or relating to Executive’s employment with the Company [. . .] shall be resolved exclusively by arbitration [. . . .] In any such dispute, the prevailing party shall be entitled to attorneys’ fees and costs, in addition to any other relief that may be awarded.

If we quote only the important words, this is all we need:

Plaintiff’s Agreement required that claims be arbitrated, and that “the prevailing party shall be entitled to attorneys’ fees and costs . . . .”

This is the hardest part of writing: reviewing our vast knowledge of a subject, including quotations, and selecting only the tiny pieces our reader needs. When we condense quotations in our own more precise words, or pare them for maximum effect, we walk the shortest path to enlighten and move our reader.

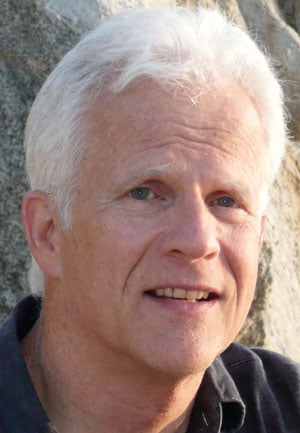

P. S. I hadn't talked to the father in over a decade. Last fall, I was in Utah, and I stopped by his home, unannounced. We sat in the same room where we had sat so many years earlier, I, and eventually the reader, listening to how he faced a tragedy unimaginable to the rest of us. At 92, he was as hale and hardy as I remember him at 52, and the visit was memorable beyond my ability to express it.