One misconception about editing is that it’s simply a function of time—that if given the same document and the same block of time, everybody would spot the same edits. That’s not true. Effective editors train themselves to spot specific edits. That is, they go into every editorial session knowing how wordiness usually arises and how to fix it. With practice and experience, those fixes become editorial reflexes.

Here are my “big four” edits for succinctness and readability. They’re hardly unique to me. I’ve learned them from others. But they’re my top picks for legal writers—the most effective edits a lawyer can learn. Watch for them in every draft. They may seem small, but their cumulative impact is big.

Edit 1: Question every of

The point: Prose suffers from needless or wordy prepositions.

The edit: When you see the word of, question it. You’ll leave many, of course, but question each one. Often you can move the preposition’s object—the word after of or of the—to serve as a possessive or adjective earlier in the sentence. (I learned this edit from my friend and mentor Joe Kimble, who helped redraft the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Evidence, among others.) Once you get used to watching for ofs, do the same for phrases like for the, by the, and more.

Example:

- The verdict of the jury shocked onlookers.

- Edit: The jury’s verdict shocked onlookers. [possessive]

- Alternate: The jury verdict shocked onlookers. [adjective]

Real-World Example:

- Wordy: The plan of the Secretary will cut the revenues of MOHELA, impairing its efforts to aid college students in Missouri.

- Better: “The Secretary's plan will cut MOHELA's revenues, impairing its efforts to aid Missouri college students.”

— Chief Justice John Roberts, Biden v. Nebraska, 600 U.S. 477, 491 (2023).

Related edit:

Downsize wordy prepositions such as in regards to or with respect to:

- We spoke in regards to about possible settlement terms.

- With respect to As for the final provision, . . .

Edit 2: Avoid Wordy Nominalizations (i.e., Buried Verbs)

The point: Strong verbs improve flow and impact. But verbs disguised as wordy, abstract nouns—“nominalizations,” as grammarians call them—turn crisp prose soggy.

The edit: Watch for nouns ending in -ion, -ment, or -ence. If that noun has buried a verb, unearth the verb and save words.

Example:

- The court reached the conclusion that the damage award was excessive.

- Edit: The court concluded that the damage award was excessive.

Real-World Example:

- The Court has never made a determination of the precise mens rea needed to impose punishment.

- Better: “[T]he Court has never determined the precise mens rea needed to impose punishment.”

— Justice Elena Kagan, Counterman v. Colorado, 600 U.S. 66, 82 n.6 (2023).

Edit 3: Avoid Rote Lawyerspeak (Prefer Confident, Direct Language)

The point: Legalese and lawyerisms are Fool’s Gold. Scholars long ago debunked the precedent myth, finding that fewer than 3% of a typical contract’s terms have any court-glossed meaning. And recycling the trappings of legal style—pursuant to, subsequent to, etc.—only blunts your message’s impact. So don’t bog down your message. Don’t succumb to habit or stuffy style. Connect with your busy readers.

The edit: Be on the lookout for legalese and needlessly inflated language such as pursuant to, subsequent to, commenced a cause of action, and many more. Replace them (as the Supreme Court justices usually do) with substitutes that are more direct: under, after, sued, etc.

Example:

- Subsequent to the meeting, the buyer commenced a cause of action for breach of contract.

- Edit: After the meeting, the buyer sued for breach of contract.

Real-World Example:

- Attributing his illness to his employment activities with Norfolk Southern, Mr. Mallory retained Pennsylvania lawyers and commenced a civil action against his former employer in Pennsylvania state court pursuant to the Federal Employers’ Liability Act.

- Better: “Attributing his illness to his work for Norfolk Southern, Mr. Mallory hired Pennsylvania lawyers and sued his former employer in Pennsylvania state court under the Federal Employers' Liability Act . . .”

— Justice Neil Gorsuch, Mallory v. Norfolk S. Ry. Co., 600 U.S. 122, 126 (2023).

Breaking down the edits:

- employment activities = work

- retained = hired

- commenced a civil action against = sued

- pursuant to = under

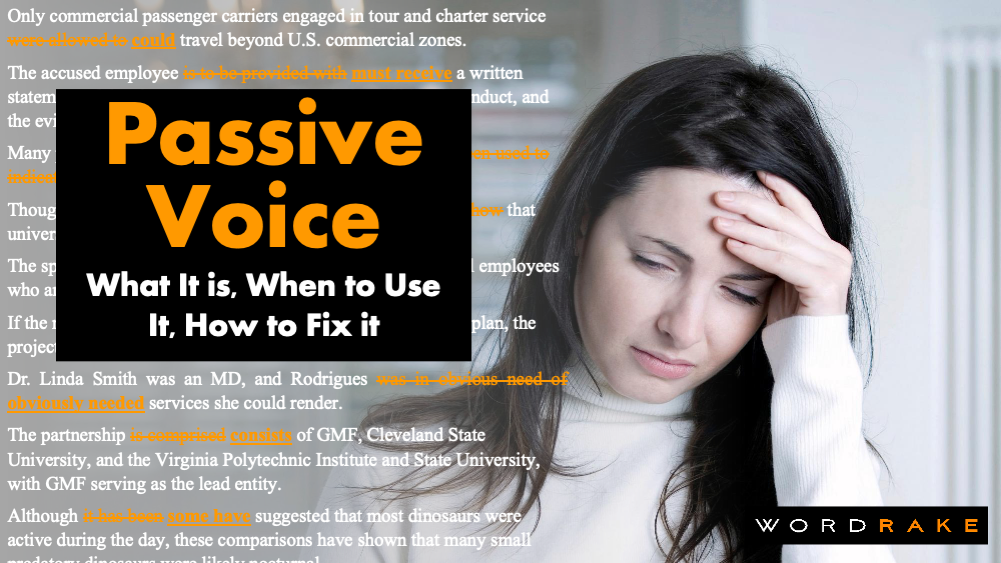

Edit 4: Prefer Active Voice

The point: Active voice is clearer and more succinct than passive voice. Active voice means that the actor (or logical agent) appears before the verb, performing the verb’s action. Passive voice—with the actor coming after the action (or not at all)—is often wordy and sometimes ambiguous. Passive voice isn’t always unclear or obtrusive, so you’ll frequently leave it. (Smith was served last Tuesday.) But active voice is a good default style.

The edit: To check for passive voice, look for the actor. If the actor appears after its action (e.g., the motion was granted by the court) or doesn’t appear at all (e.g., the motion was granted), then the clause is passive.

Example:

- The contract was signed [action] by the parties [actors] on January 15, 2020. [passive]

- Again: The contract was signed [action] on January 15, 2020. [passive, with implicit actor or actors]

- Edit : The parties signed the contract on January 15, 2020. [active]

Real-World Example:

- At sentencing, two of Lora’s arguments about his § 924(j) conviction were rejected by the District Court. [The court appears after its action.] Most pertinent here, it was argued that [Who or what argued? Where is the actor?] the District Court had discretion to run the § 924(j) sentence concurrently.

- Active voice: “At sentencing, the District Court rejected two of Lora's arguments about his § 924(j) conviction. Most pertinent here, Lora argued that the District Court had discretion to run the § 924(j) sentence concurrently . . .” [active voice in both emphasized clauses]

—Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, Lora v. United States, 599 U.S. 453, 455–56 (2023).

Again, the passive voice is sometimes understandable and inoffensive. It might even be strategic. But more often, your switch to the active voice will pay dividends.

Spotting passive voice is challenging and takes practice. In fact, each these “big four” edits takes practice. But if you keep them in mind every time you edit, you’ll quickly improve. They’ll start to jump off the page at you. And you’ll soon see the difference in your writing—as will your readers.

About the Author

Mark Cooney chairs the writing department at Thomas M. Cooley Law School. He was Editor in Chief of The Scribes Journal of Legal Writing for six volumes and now serves as a Senior Editor. He is author of Sketches on Legal Style (Carolina Academic Press 2013) and coauthor of The Case for Effective Legal Writing (Carolina Academic Press 2024 — forthcoming). He has published more than 50 articles or book chapters on legal writing and other topics. His works have appeared in The Green Bag, Legal Communication & Rhetoric: JALWD, the Scribes Journal, and elsewhere, and have been quoted and cited by state and federal courts.

.png)